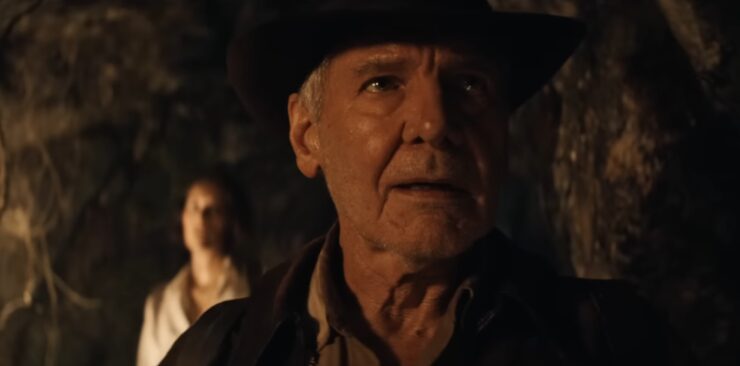

It is clear that the fifth (and final, if Harrison Ford and Lucasfilm are to be believed) Indiana Jones serial intends to be a “return to form” right from the opening credits—which pointedly use the exact same font as the opening credits of 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. (The irony of trying this move when the very first sight in the film is Disney’s 100th anniversary logo cannot be overstated.) This would seem to be a bit of wishful thinking on the part of director/co-writer James Mangold, the man who Hollywood has decided should be the go-to for aging heroes and their final chapters, after his success with X-Men’s Logan.

Dial of Destiny is by no means a return to form. It’s only half of a good movie, in fact. But that half, funny enough, is still lingering in my mind.

[Some spoilers for Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny]

The amount of time the production spent trying to assure audiences that Ford’s CGI’d de-aging would be seamless during the film’s half-hour (half-an-entire-damn-hour for some reason) 1944 opening sequence… should have been our first clue that it would be the opposite. The technology has certainly stepped up—something I’m not in favor of regardless, on both ethical and creative fronts—but it’s still deeply imperfect, often uncanny, and badly grafted at key angles. This makes the overlong start to the film muddy in all the places where it needs to be sharp, specifically the action itself, which is often too dark to parse (an increasingly common issue in modern cinema), too fast to follow, and too packed to make an impression.

While the whole segment could have easily been cut down to half the time or less, it offers up our relevant Macguffin for the journey: the antikythera, or Archimedes’s Dial, an ancient device that can supposedly detect fissures in time. This makes it of particular interest to Jürgen Voller (Mads Mikkelsen), a Nazi mathematician who hates Hitler for losing their war—because he could see all the errors all too clearly, and knew how to win. Luckily, Indy and his pal Basil Shaw (Toby Jones) make it out with the half of the dial uncovered by Voller. Unluckily, Basil’s possession of the artifact drives him to obsession and mania, and then a premature death.

He leaves behind a daughter named Helena (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), who shows up at Jones’ doorstep on the eve of his retirement—which is also Moon Landing Day—to get the dial half Indy eventually wrested from her father for his protection. But Voller has been working in the U.S. under the auspices of Operation Paperclip, and is also seeking what Jones stole out from under him twenty-five years ago. Helena’s motives are also far from familial and fond despite being Indy’s goddaughter; turns out that she wants the dial to sell it at auction in Tangier, having fallen into a somewhat murky lifestyle following her father’s death.

The racism that is unfortunately a hallmark of the series remains intact, even in its attempts to do better. While a scene where Indy cracks a whip in a Tangier hotel and is met with a dozen guns—a clear jibe at his own dispatch of the skilled swordsman in Egypt during Raiders—is meant to show that filmmakers have perhaps learned a lesson or two, it doesn’t change the fact that the very first shot of people in the city is a local woman being sexually harassed by a local man in a sweeping shot across said hotel. Nor does it make up for the film offering us Shaunette Renée Wilson’s excellent turn as government agent Mason, only to cruelly discharge her from the narrative because… I guess we needed another reminder that Nazis are evil?

There are a few other moments of correction, like the whip in the hotel—an awareness that runs through the film about past slights or common themes that should be addressed. There’s a moment where Helena and Indy get covered in bugs, much like poor Willie in Temple of Doom, and the film goes out of its way to show them both panicking to a very vocal degree, thereby retroactively rendering Willie’s screams as anything but an overreaction. (Which, they never were, for the record.) There’s a moment where Indy asks Helena why she would chase down the thing that drove her father mad, and she stares him in the face and asks “Wouldn’t you?” because this is a series about the obsessions and knowledge and life pursuits we inherit, and how they shape us. There’s also the relationship between Helena and her literal partner-in-crime Teddy Kumar (Ethann Isidore), a clear harkening to Indy’s relationship with Short Round (the duos even met the same way), but unlike Shorty’s disappointing evaporation from the series, it’s clear that Teddy will be folded into Helena’s life for the long-haul by the end.

Buy the Book

The Archive Undying

There are plotholes aplenty in this one, so if you’re hoping for sense (or even sensibility), consider this fair warning. The CGI genuinely does drag the film down at key moments when emotion is running highest, and it’s something that Hollywood needs to pay attention to and reconsider heavily in the future. There’s a particular conversation toward the end of the movie that takes place on a beach, and the background is so clearly manufactured that it renders everyone’s hair blurry, the lighting a sad mockery of true daylight. It’s frustrating to be watching an effort that took nearly three-hundred million dollars to put in front of an audience, and be sitting there thinking why couldn’t you have just put these people on a real beach? when you’re meant to be invested in the character’s emotions.

There’s an argument to be made, too, about how we frame action sequences as actors age. Jones is supposed to be a pretty wily guy who’s mostly clever to win his fights, despite being able to take a punch, yet he’s seventy years old here (and Ford is eighty). There are moments where the film allows this to be true, to watch him struggle when attempting to wrestle with Voller’s muscle (Olivier Richters), knowing that he can’t take a man that large at his age, even if he had the time to be clever. But because Ford insists on playing to realism in those moments, it changes the nature of the blows—it’s not “fun” to watch an elderly man get punched in the face. And he does, repeatedly. And if the film had been a little smarter, it might have really used that, made something of our love for carnage when we don’t perceive the person taking the hits to have any real-world frailties. Indiana Jones does, and it’s not going to feel the same now when someone socks him on the jaw.

Having said all this, there are many places in this film that truly do “get” this character beyond his sordid grave robbing moniker and the colonialist baggage it rightly brings. Because at his core, Indiana Jones is plainly just… a history nerd. That is what matters to him, what he cleaves to. His catchphrase of “That belongs in a museum!” (which makes another appearance here) is always made in direct reference to people who are stealing artifacts for profit, to put in the hands of private collectors. Despite the blindspots of this cry, to him, it is ultimately a call for history to be treated with the collective respect it is owed, and shared as widely as possible. The day of his retirement is flooded with New Yorkers of every stripe ignoring him in favor of the moon landing, and while that’s hardly surprising, you can see in Ford’s expression precisely what Indy is thinking of all this: How heartbreaking that everyone is looking to the stars when what we’ve got right here on our own planet is infinitely fascinating, complex, and worthy of awe.

Strangely, that’s a thought we could all stand to internalize right now.

There’s also an acknowledgment of the enduring affability of Indiana Jones, being his propensity for gathering friends to him like an ungainly pile of lucky charms wherever he goes. The film builds on this ever-expanding cadre of friends all over the globe: We see Sallah (John Rhys-Davies) again, whose family Indy helped bring to America during the war to keep them safe; we learn about Basil; and we meet Renaldo (Antonio Banderas), a diver in Greece who helps them retrieve the next piece of the dial’s puzzle. We watch Indy renew his relationship with Helena, and find that he’s somehow able to bring out the best in both her and Teddy. And we learn what breaks that seeming superpower; his separation from Marion Ravenwood is a sore spot throughout the film, and there are painful reasons in it that he is barely able to speak of.

Given the recent slate of films on the subject of heroes giving their last hurrahs, we would obviously expect the same ending for Jones—only to have the film violently oppose that idea. After Professor X and Logan, after James Bond, after Tony Stark, and so many others doing the so-called noble thing and leaving behind families and friends again and again because heroism is about great deeds at all costs and certainly not about growing old with the ones you love, the Dial of Destiny roundly says… no.

No, that’s not good enough. No, that’s not the point of having a life. No, that’s not what we want for this grumpy old nerd who just wants someone to read and annotate ancient texts with until he dies. Helena is a wonderful character in her own right, but she becomes something of an audience stand-in at that moment, giving Indy the answer we might offer: You are here for the people who love you. There are far too many of us for you to pack it in. (She couches it in protests against temporal paradoxes, though, which is right smart of her.)

Okay, so the first half enraged me, but the ending did make me cry. As a send-off, I can’t ask for much more than that, I suppose. And we did get one more John Williams score out of it.

Emmet Asher-Perrin thinks a lot about the number of archaeologists who caught the obsession from Indy directly, and thinks that’s a perfectly good legacy, when all is said and done. You can bug them on Twitter and read more of their work here and elsewhere.